For all of you who have taught students, you know that one of the rewards is seeing the “Aha moments” that students experience. One of the downsides (to instructors) of teaching online is that it is hard to “see” the reward of the “aha” in the same fulfilling way.

The reason we should care about the aha moments that students experience is that this kind of moment is tied closely to an emotional feeling. And memories with emotional attachments tend to be stronger (more memorable) than ones with no emotional attachment.

But have you ever stopped to think about what is going on right before the aha moment? Does the aha moment come after a well-organized lecture, a step-by-step example, a period of boredom, or a period of confusion or frustration?

An aha moment typically comes after a period of confusion or frustration. This means that you have to put students into that space where they are actually at the edge of what they know (the confusion/frustration space) to nudge them over to insights.

Anyways, I digress. I want to share findings from this paper: Better to Be Frustrated than Bored: The Incidence, Persistence, and Impact of Learners’ Cognitive-Affective States during Interactions with Three Different Computer-Based Learning Environments (Baker, et al, 2010).

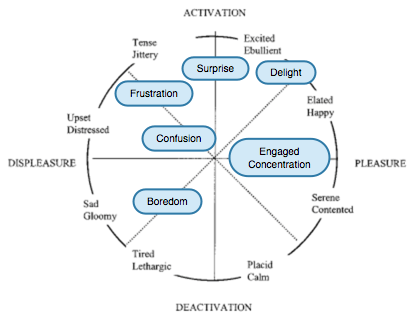

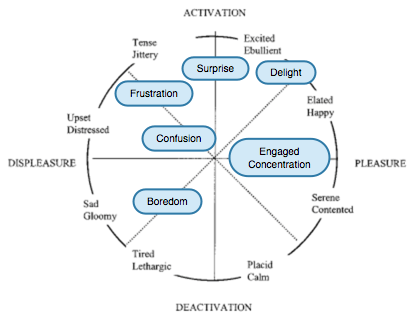

The researchers set out to focus on cognitive-affective states that were hypothesized to influence cognition and deep learning: boredom, confusion, delight, engaged concentration, frustration, and surprise. The researchers use Russell’s Core Affect framework (2003) to map these states in two dimensions: valence (pleasure to displeasure) and arousal (activation to deactivation).

In this study, the researchers examined:

- the cognitive-affective states the students experienced during the learning process

- how those states persist over time (e.g. do students move from boredom to frustration more often than frustration to boredom?)

- how the state affects the students choices on how to interact with the system (e.g. what causes students to game the system?)

While I will leave you to read the whole paper if you want all the details (the methodology involves three different interactive learning systems and three different methodologies), I think the nuance of definitions between a few of these terms is important. As defined in the paper:

- frustration is dissatisfaction or annoyance

- confusion is a noticeable lack of understanding

- engaged concentration is a state of engagement with a task such that concentration is intense, attention is focused, and involvement is complete

Now let’s jump ahead to (what I consider to be) some of the interesting results. Engaged concentration was the most common state during the observation periods (60%) followed by confusion (13%). While boredom was only observed about 4-6% of the time, it was also the most persistent state (once bored, the student stays bored) across all three learning systems.

Within two of the systems where “gaming the system” was observed, a more in-depth analysis was performed. Boredom was significantly more likely to lead to gaming the system. Guess what wasn’t likely to lead to gaming the system … confusion, frustration, and surprise. Better to be confused than bored, huh?

There is quite a bit of new research being performed on the role of confusion in learning, but my gut feeling here is that confusion leads to self-insight, and learning gained through self-insight (because this is the aha where emotions are attached) should be stickier than learning delivered through other states.

Challenge: Vigilantly watch for states of boredom in your classes, and when you find them, intervene. Do something different. Put students into a space where they are challenged and maybe even a little confused. Give the learners a chance to grapple with the concepts and have those moments of self-insight.

Reference:

Baker, R. S., D’Mello, S. K., Rodrigo, M. M. T., & Graesser, A. C. (2010). Better to be frustrated than bored: The incidence, persistence, and impact of learners’ cognitive–affective states during interactions with three different computer-based learning environments. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 68(4), 223-241.